This continent was built on manufacturing, but we somehow got lost along the way. I believe it’s time to focus again on what really matters.

My buddy Chris edited this version of Unbeaten Path with the help of the Rolling Stones “Exile on Main St.”

To succeed in VC, you need to understand your role in the food chain.

The following chart was posted by Perplexity’s founder, Aravind Srinivas, and it says one very simple thing: if you are a small early-stage fund, your alpha is not in what’s hot today, but rather in what’s going to be hot tomorrow.

I love this quote from a recent Euclid Venture’s Substack post because it feels so obvious, but yet many managers of “small” funds seem to forget it.

Large funds can do things emerging managers simply can’t. They have the ability to make a multitude of early option bets while reserving the vast majority of their capital for later stages. While their investment roadmaps are well publicized, they are, of course, influenced by what they want to invest in today (at Series A-Growth). Emerging managers, whose first checks are usually their most significant driver of alpha, should be concerned with what will succeed—and hence attract downstream capital—tomorrow. And a lot changes in one year, let alone three, four, or five years down the line.

Following this reasoning, to succeed as an emerging manager one has to start from first principles, wearing some hype-filtering glasses and looking at what the world will need tomorrow.

So here’s my attempt! An absolutely incomplete list of observations that should help me understand what are the real needs of Europe for the next 10 years.

Industrial is big, Software is small

The first observation is somewhat obvious: Europe is strong in manufacturing, and is weak in software.

If we look at the European [UK included] public companies worth more than €100B, only two are software companies (SAP and Spotify) while the great majority of them are in the broad category of industrial and manufacturing: ASML, Siemens, Schneider Electric, Airbus, Arm, just to name a few.

In 2025, European software market revenues are forecasted to reach $166.5B, with enterprise software projected at $70.6B. For the same year, software revenues in North America are projected at $407.2B and those of enterprise software at $171.2B - around 2.5x that of Europe(source)

On the flip side, Europe’s manufacturing output is slightly bigger than the US’ ($2.7T vs $2.5T). European industrial sectors have fueled the growth and wellness of its biggest countries for decades, and created ecosystems of skilled workers that should constitute competitive advantages over competing regions. It’s not by chance that SpaceX and all the new US space startups are in El Segundo, an area where companies like Boeing and Northrop Grumman have had production facilities for decades.

These are obviously just two measures that don’t paint the whole picture. There are factors that we all know have an impact - like the US is one big market while the EU is the sum of small markets.

Another consideration is that big public companies don’t necessarily imply better liquidity options for startups. What they do imply though is either more revenue options, or better future revenue options, or better quality of the revenue (depending on your preferred method for valuing a public company). These factors generally should imply better companies to invest in.

Sometimes hard questions have simple answers, and in this case the simple answer is this: a big market makes a better market than a small market. In Europe, industrial is bigger than software.

The West is losing its ability to manufacture

However, there’s a problem: the West is slowly losing its ability to manufacture things.

We started with outsourcing low-value added industrial processes to countries far away, because it was cheaper and hey, who wants to produce steel anyway?! I’d rather write software!

The problem is that low-value added industries advance into high-value added industries, there is technology spillover, and suddenly the workers we once considered cheap labour are better than us in high-tech industries.

We forgot how important the industrial sector is, and acted like enterprise software could solve all the world’s problems. Unfortunately this is rarely the case, and we found ourselves with 20 years of zero productivity growth, and a bunch of problems that need to be solved in the physical world - energy, infrastructures and defense to name a few.

How can we fight climate change, if we can’t build nuclear plants anymore? How can we fight our enemies, if most of the drones are produced by the enemy?

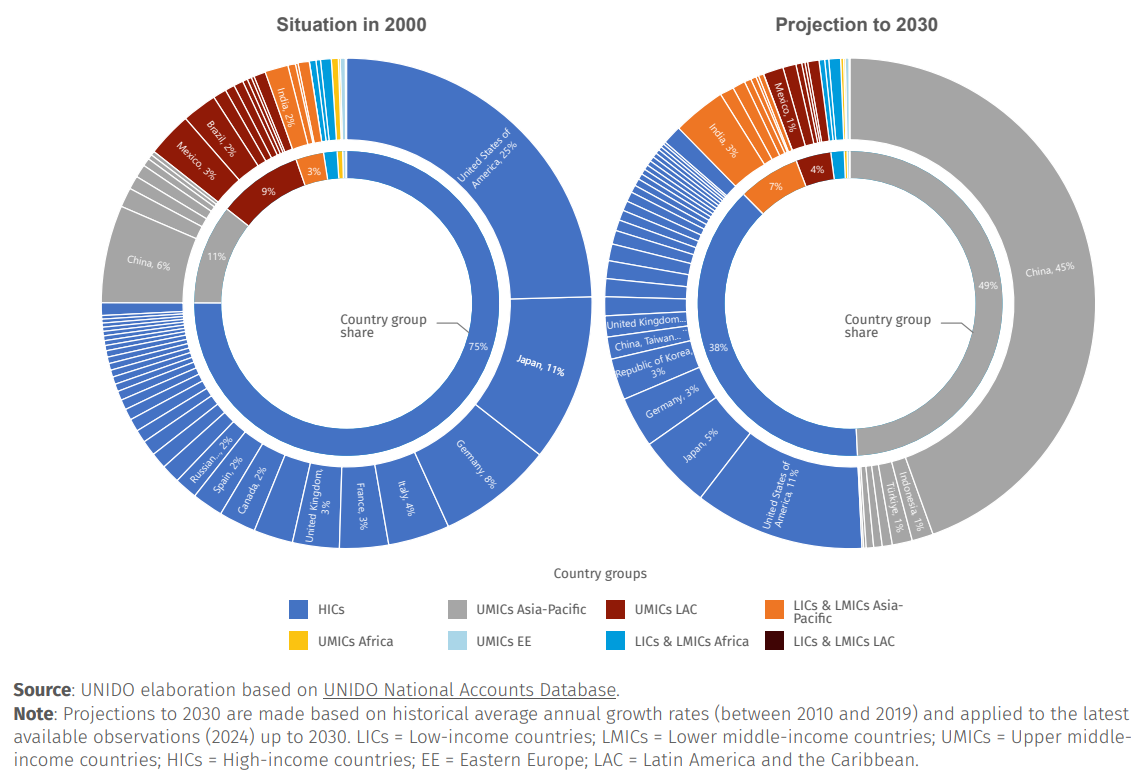

When I say the West is losing relevance, don’t rely on my words, trust the numbers:

China holds more than 80% of global solar manufacturing capacity - source

China and South Korea secured more than 80% of global orders for new ships in 2023. Europe has 7%, most of which cruise ships - source

China produces enough batteries to meet all its internal demand, and export around 12% of its production. Europe imports more than 20% of its demand, USA more than 30%. In Europe, 75% of production capacity is owned by Korean companies, with 50% by LG alone - source

There are only five nuclear reactors being built in Europe - 2 in Ukraine, 2 in the UK and 1 in Slovakia. There are 57 being built in the rest of the world, with 28 in China and 7 in India - source

China has 76% of global electric car market share - source

In 2023, China produced around 54% of world’s steel, Europe 7% and USA 4% - source

I’ll stop here, but I could go on and on - the more I search, the more I find.

Europe stopped growing, but we shouldn’t give up

Why do we care so much about manufacturing?

What we really care about is quality of life, and that’s very much related to productivity.

Aggregate productivity level of a country is determined by the productivity level of individual industries: when countries move from being manufacturing economies to being service economies, the average productivity level decreases.

Manufacturing sectors benefit from economies of scale - the more you produce, the better you are at doing it, and the more productive you become. Being more productive enables better economics, which can be reinvested into R&D powering a positive flywheel. Economies of scale enable better productivity levels, meaning that inputs (labor and capital) are transformed more efficiently into outputs.

This, however, does not apply to service economies, and is why it’s bad that we abandoned manufacturing.

So, why shouldn’t we give up?

I believe the VC industry should be obsessed with inflection points - the famous Why Now. The good news here is that I see several inflection points that could help change the slope.

First one is geopolitics. Sometimes geopolitics can be stronger than economic reasons and, when it’s not, politicians can weaken the economic reasons with tariffs.The West didn’t find itself in this situation overnight, but gradually arrived here because of economic reasons. Doing stuff in the East was cheaper. Now we realize how big of an error it was, and governments on both sides of the ocean are pushing toward a re-shoring of industrial technologies (”American and European dynamism”). Focusing on Europe, it seems that finally the wake up call is being heard and many important initiatives are gaining traction to make Europe a more “innovation friendly” continent - we should keep pushing.

Then, there is energy. Price has been one of the most competitive disadvantages of European manufacturing businesses in the last decade. Our energy mix was very much skewed towards imported gas, and we were pure price-takers. Unfortunately (or luckily, maybe) we were forced to change in a moment in time when renewable energy is cheaper than ever and nuclear power is gaining momentum again. There are enormous challenges to overcome - we are slow in building nuclear facilities because we haven’t built any in a while, the supply chain of solar is a near-monopoly of China, same for batteries. However, each challenge is also an opportunity: when dealing with commodities, the only way to reduce price is to produce more affordably, and technology is the right way to go.

The last inflection point is automation. Robotics has been so far constrained to the dull, dirty and dangerous. Robots today are not different from the Unimate installed in General Motors’ factory in 1961. But with AI, this is changing. Now robots can understand the real-world, which means they can interact with it. This opens unlimited new tasks to automate. Europe (and the West) is aging rapidly, and the only chance we have to survive is to become more efficient at producing things: we are lucky that automation is getting smarter and smarter.

The role of venture capital

I started this rambling monologue talking about alpha, so the million-dollar question is: are the above-mentioned problems “venture-backable” ones?

I believe they are.

One of my favorite thesis is Union Square Ventures’ “Investing at the Edge of Large Markets Under Transformative Pressure”. This thesis has everything that a perfectly crafted thesis should have: it’s broad enough not to apply only to a very narrow market or particular point in time (we still want diversification, and funds have a lifespan of 10 years), but it’s specific enough to drive decision making coherently.

Well, allow me to learn from the best and steal some of their ideas to prove my point.

New technologies enable behaviors that weren’t previously possible. In hindsight, these new behaviors are obvious, but they require experimentation to explore as they emerge. Rapid experimentation is the fastest path to progress – but change is hard. Institutions and incumbents resist it.

“Edge” approaches […] have the potential to avoid market gatekeepers and enable freer experimentation. We love them for this reason.

The problem with industrial applications is that they have enormous inertia: they require capex and know-how and working capital and on and on. How do you overcome this process as a startup?

You start from the edge of the industry you are disrupting and you leverage technology to move fast. That’s what startups do best, and what big incumbents are very bad at doing.

However, established market positions are established for a reason: they are hard to move. Unless something changes, unless there are inflection points.

Technological and societal pressures can upset existing market structures, creating openings for new companies and networks to meet the market in new ways. […] Together, these pressures can cause otherwise static market structures to become dynamic. Startups have the opportunity to position themselves in alignment with these pressures, allowing themselves to work “downhill” against legacy incumbents

These “pressures” are what I have described above, and startups that understand and ride these pressures will work downhill.

We need defense but defense is broken? Solve that, and you become Anduril.

We need access to space but access to space is broken? Solve that, and you become SpaceX.

We need solar, we need steel, we need precision-parts manufacturing, we need nuclear, we need semiconductors. Solve that, and you become the next big industrial company in Europe.