Startups, productivity and fertility rates

#6 | On why startups are good for our living standards.

This issue is very close to my heart, as it should be to every European.

Are we doing enough to let innovation thrive? What are the consequences if we don’t put enough effort into R&D?

Chris chose US DnB to edit this week’s Unbeaten Path!

“GDP per capita = living standards”

These five simple words that sum up so much of our world were, in fact, the title of the first slide of a macroeconomics class about growth I attended some time ago.

To this day, I still recall everything about that lecture. Perhaps thanks to my excellent professor, or maybe because my motherland - Italy - hasn’t really grown much since I was born in 1993.

Before identifying possible solutions, let’s double-check that our equation holds true. After all, how do you even define living standards?

Our perception of the world is often wrong, so we need numbers to understand what’s really happening, as Hans Rosling explains in his book Factfulness (a recommended read).

Luckily, Our World in Data provided the following.

As these graphs show, GDP per capita has a pretty evident correlation with many aspects that define living standards - from life expectancy and child mortality, up to literacy rate and life satisfaction.

Or to put it bluntly, during the years when GDP falls, the death rate rises by 0.4 deaths per 1,000 people, according to the Bank for International Settlements.

How do we grow GDP per capita?

Now that we know that expanding GDP per capita improves living standards, what can we do to achieve that?

First things first, definitions!

I like this decomposition because it gives clarity on the three main factors that influence GDP per capita:

Productivity - how much we can produce per every hour we work.

Effort - how much we are working per day.

Demographics - what is the percentage of the population in the working age, i.e. neither too young nor too old.

These factors should help countries plan a strategy to achieve growth.

The EU has a big demographic problem. There are fewer and fewer births, which means the “demographics” part of the equation is also shrinking.

To counterbalance the demographic effect, we have three options.

The first one is to add more people of working age. Europe has leveraged this for many decades but the rise of populist politics throughout the continent has made it an unpopular option. For what it's worth, of the 446.7 million EU citizens, just 5.3% were born outside of the EU, according to the European Commission.

So, politics aside, we could either increase effort - not a good strategy for many reasons that can be explained another time - or increase productivity.

Increasing productivity is the most attractive option to me.

How do we increase productivity?

This is the million-dollar question.

Looking at the numbers, productivity growth has slowed in most “mature” economies. And this is a big problem.

But why is that?

It’s often impossible to find a single reason to explain macroeconomic effects, however, an important culprit is technology.

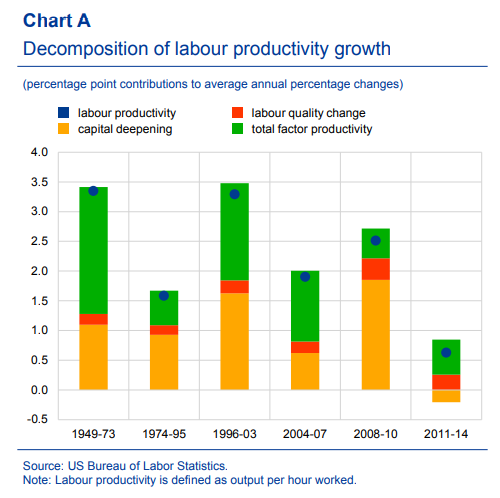

The picture above shows US productivity growth in its main components. What interests us is the green bar: the total factor productivity.

This “captures the increase in efficiency [...] which is due to other factors such as new technologies, more efficient business processes, and organizational improvements.” (source).

In the 20th century, new technologies such as the telephone, internal combustion engines, industrial automation in the assembly line, radio, and air travel greatly contributed to productivity growth. After a brief slowdown in the last quarter of the century, the 21st century leaped forward with the advent of the internet and more sophisticated telecommunications. Think mobile phones, satellites, and 5G.

However, since then, technology has not contributed much: somehow we stopped disrupting industries with new inventions and, instead, we focused more on incremental improvements.

Sure, Slack increases the speed of communication, but how different is it from an email?

We need more Research and less Development

R&D stands for Research and Development. If that’s blindingly obvious, bear with me.

I always considered R&D as a unique practice, until I read a paper by researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM).

R&D can in fact be divided into two distinct components, research and development, and not a buzzy catchall you see on a corporate balance sheet.

Research “involves analyzing fundamental principles and phenomena, and it often aims at generating new ideas and testing hypotheses without a specific application in mind”, while development “usually starts from an existing ‘proof of concept’ and aims at improving specific products, processes or services”, according to the TUM team

Using this definition, the authors show that the share of a firm’s R&D budget that’s devoted to research declines as the firm grows. Moreover, by analyzing total factor productivity estimates (remember, the green bar from above) they proved that “research is a key driver of productivity”.

So far, so good. Small firms (we call them startups) invest in fundamental research, they get acquired by big firms (we call them exits) and the fundamental research moves into the development phase. This process allows the broader community to benefit from these productivity gains via an increase in GDP per capita.

This is why it’s worth investing in startups, and a healthy startup ecosystem is good for the economy.

Unfortunately, we have a problem.

Old people don’t start new companies

Beginning in the late 1970s and continuing for the next three decades, there was a consistent annual decline in the number of new businesses being established in the United States.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York, using its proprietary data, analyzed why and published a worrying report in 2019. It showed that what they call “startup deficit” - 60% of it, to be precise - can be attributed to demographic reasons.

Put simply, the data show that a declining labor force equals a lower startup rate.

This is a worrying result for the Western world, as we are living in a demographic crisis that will severely impact the labor force size in the coming years.

As we have shown above, a country with good living standards is a country with a high GDP per capita. To have a high GDP per capita we need increased productivity, which is pushed by research performed by young firms.

If it’s true that old people don’t start new companies, then the Western world will have a hard time increasing its living standards in the future.